Many children with early onset scoliosis look and function fairly normally. If the curves are mild, it can be very difficult to distinguish a child with early onset scoliosis from children without spinal deformity. The key to evaluating for a curve or curve progression is to pay close attention to symmetry:

- Shoulders should be level

- Shoulder blades should be the same height and shape

- Spine should run down the center of the back

- Head should be centered over the pelvis

- Head should be level

- Waist should have symmetric contour

- Hips should appear level

- There should be no abnormal fullness in one side of the thoracic or lumbar spine on standing or when bent over at the waist

- They should not lean to one side

A well performed and documented neurological exam is mandatory in the evaluation of any child with scoliosis, but this is especially true of children with early onset scoliosis. When able, a complete sensory and motor examination should be performed with graded motor strength. Additionally, all major reflexes should be evaluated including abdominal reflexes. Back pain is generally not a significant complaint unless the curve is quite large. Likewise, numbness, weakness or loss of bowel or bladder control would not normally be expected. If these symptoms do appear, emergent evaluation in the emergency department is essential.

Imaging

In the evaluation of a child with early onset scoliosis, imaging will be required not only to understand the nature of the problem but to follow progression over time. The best imaging modality is the standard x-ray. The appropriate image to order is the full length PA and lateral x-ray of the thoracic and lumbar spine taken in the standing or sitting position if possible. It is helpful to include the upper portion of the pelvis as well as the shoulders for the purpose of evaluating sagittal and coronal balance. The Cobb method of measuring curve magnitude in the sagittal and coronal plane is generally preferred

Advanced imaging is usually ordered at some point for these patients. This might include a CT scan to evaluate bony anatomy in congenital curves or for surgical planning, or an MRI to better access for intracanal pathology. Typically these should be ordered by the treating orthopaedist or neurosurgeon

Associated Conditions

There are a number of conditions associated with early onset scoliosis. When taking care of children with these known issues, care should be taken to pay close attention to their spine. The following list includes several conditions known to have early onset spinal deformity. It is by no means complete, and conditions not on the list can still have associated spinal anomalies and progressive deformity.

- Cerebral palsy

- Chiari malformation

- Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

- Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease

- CHARGE syndrome

- Down's syndrome

- Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Escobar's syndrome

- Familial dysautonomia

- Friedreich's ataxia

- Fragile X syndrome

- Hemihypertrophy

- Marfan's syndrome

- Muscular dystrophy

- Nail–patella syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Prader–Willi syndrome

- Proteus syndrome

- Spina bifida

- Spinal cord tether

- Spinal muscular atrophy

- Spinal tumors

- Syringomyelia

- Trisomy 8

Etiology

The underlying medical conditions of patients with early onset scoliosis help determine the prognosis and treatment. Some patients with neuromuscular conditions such as cerebral palsy or spina bifida have a very different treatment plan than patients without other medical problems. This is true even if the scoliosis appears similar in shape and size. In this section we will discuss a variety of conditions that are commonly associated with early onset scoliosis.

There are several sub-categories of early onset scoliosis that are commonly recognized. These include:

- Neuromuscular

- Syndromic

- Congenital

- Scoliosis associated with tumors, infection, and prior surgery or trauma

Neuromuscular Scoliosis

These are patients who develop scoliosis in association with conditions that affect their muscles or their nervous system. These might include the following:

- Muscular dystrophy

- Congenital myopathies

- Hypotonia

- Chiari malformation

- Cerebral Palsy

- Spina Bifida

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

- Polio

Patients who are diagnosed with any of the conditions above may have higher rates of scoliosis, have an increased likelihood of a more progressive curve, and be less responsive to non-surgical treatments such as bracing or casting.

Syndromic Scoliosis

Syndromic scoliosis is associated with specific underlying syndromes and genetic conditions. Some of these conditions affect the bones, such as osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease). Other conditions affect connective tissues, such as arthrogryposis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, or Marfan syndrome. There is also a group of conditions associated with spinal deformities but it is not yet known how they affect the spine. These conditions include neurofibromatosis and a group of conditions called the mucopolysaccharidosis, which includes Hurler Syndrome.

Congenital Scoliosis

Congenital scoliosis is a deformity that is present before birth. In this condition, one or more bones in the spine are severely malformed or missing. This is not technically a subset of early onset scoliosis, but rather its own category. Spinal deformities in these patients have different treatments and prognoses based on the severity of deformation of the bone or bones, the pattern of deformity and whether the abnormal bones become more deformed as the child grows. Congenital scoliosis cannot be corrected with bracing or casting, but may be recommended for patients as a means to delay the curve progression and allow for growth and development prior to surgery. If the curve is large enough and/or worsening, there are very limited treatment options that don't involve surgery. Fortunately, many of these patients never get worse and therefore never need surgery. If your child is diagnosed with congenital scoliosis, it is also important that you request an evaluation of their kidneys and heart as these organs are formed at the same time as the spine and commonly present problems.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

Patients with idiopathic scoliosis have scoliosis without any of the other conditions discussed above or any other known reason. This is one of the most common forms of scoliosis in early onset scoliosis. Without treatment, the curve of the child's spine has a very high chance of progressing, causing many physical difficulties such as restricting lung development and function. Fortunately, idiopathic scoliosis seems to respond better to treatment than other forms of scoliosis and the chances of complications decrease with proper treatment.

Treatment

Why Treat EOS?

We treat early onset scoliosis for a number of reasons. The curves that these children have are often very aggressive and progress rapidly without treatment. Aside from the obvious deformity and aesthetic issues, as the curves progress in magnitude, they can deform the chest wall and can eventually cause problems with development of the lungs and other end organs. This can result in failure to gain height and weight, and in severe cases can result in decreased life expectancy. As a consequence, growth sparing treatments have been developed to try to control the progression of deformity while allowing the spine to grow. Additionally, as these children reach skeletal maturity, most will need some type of definitive fusion of the spine to prevent progression into adulthood. Larger, stiffer curves that were not managed as children are very difficult to correct and are at a significantly higher risk of neurologic injury during these surgeries. By controlling the scoliosis earlier, the final curve correction is often better and almost certainly safer.

We treat early onset scoliosis for a number of reasons. The curves that these children have are often very aggressive and progress rapidly without treatment. Aside from the obvious deformity and aesthetic issues, as the curves progress in magnitude, they can deform the chest wall and can eventually cause problems with development of the lungs and other end organs. This can result in failure to gain height and weight, and in severe cases can result in decreased life expectancy. As a consequence, growth sparing treatments have been developed to try to control the progression of deformity while allowing the spine to grow. Additionally, as these children reach skeletal maturity, most will need some type of definitive fusion of the spine to prevent progression into adulthood. Larger, stiffer curves that were not managed as children are very difficult to correct and are at a significantly higher risk of neurologic injury during these surgeries. By controlling the scoliosis earlier, the final curve correction is often better and almost certainly safer.

The evaluation and management of early onset scoliosis is a complex and evolving field. The care of the growing spine with scoliosis is a dynamic and often unpredictable challenge. Significant advances have been made over the last decade and many more are on the horizon. As we better understand the nature of these curves, we hope to continue to make advances that will provide better outcomes for these children.

Non-Operative

Observation

Observation is often recommended for children with early onset scoliosis. For young infants with no congenital malformations there is up to 80-90% resolution of scoliosis. It is still worthwhile to refer to a pediatric spine specialist, because there are certain radiographic and clinical features in infants that indicate high risk of progression. These children often can be successfully treated with serial spine casting.

Children with congenital scoliosis also are often observed when they are young. The risk of progression and rate of progression will vary based on type of congenital scoliosis. Referral to a pediatric spine surgeon is advised, as children will require unique care based on their individual deformity.

Other varieties of early onset scoliosis also may be managed with observation initially even if surgery is anticipated. This generally is done to allow for additional longitudinal growth and pulmonary development as long as possible prior to attempting to alter the natural history with casting or surgery.

Casting

Casting is increasingly being utilized for the treatment of early onset scoliosis. A cast is used to guide growth of the scoliosis into a straight spine, similar to how a crooked plant can be made to grow straight by tying it to a stake.

Casting is increasingly being utilized for the treatment of early onset scoliosis. A cast is used to guide growth of the scoliosis into a straight spine, similar to how a crooked plant can be made to grow straight by tying it to a stake.

For some children, however, casting is used as a means to prevent or delay progression of scoliosis. This is especially true in cases of children with congenital spine and chest deformities, or scoliosis related to syndromes. Casting for infantile idiopathic scoliosis has variable success rates in the reported literature. Children who typically have better results with casting start with smaller deformities and at a younger age. If the scoliosis can be corrected to less than ten degrees most physicians will transition to a brace for a variable period of time and observe before declaring the scoliosis "cured".

Recent data has also demonstrated the effectiveness of casting in delaying need for operative treatment up to 3 years even in children with congenital, syndromic, and high magnitude deformities

Application of a spine cast is done in a procedure center or operating room under anesthesia. Intubation is recommended due to the elevation in inspiratory pressures required for ventilation while the cast is being applied. No incision is made. Casts are typically changed every 2-4 months based on the child's age (longer interval as children get older). Some doctors place casts that go over the shoulder, some do not go over the shoulder.

Related Reading

Bracing

Bracing is also used for management of early onset scoliosis. There is less data on the effectiveness of bracing for early onset scoliosis compared to casting. Often bracing is used in conjunction with casting either during summer "breaks" or after your child's spine has straightened with casting.

VEPTR & Growing Rods

VEPTR™

VEPTR™ stands for vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib. It is a device that was developed to treat children with severe malformations of their chest and spine. It is an FDA approved device. VEPTR™ is now used for various spinal and chest deformities in young children.

VEPTR™ stands for vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib. It is a device that was developed to treat children with severe malformations of their chest and spine. It is an FDA approved device. VEPTR™ is now used for various spinal and chest deformities in young children.

The VEPTR™ was initially developed in San Antonio by Dr Robert Campbell and Dr Melvin Smith for children born with multiple fused ribs and spinal deformities related to syndromic conditions such as Jeune's syndrome and Jarcho-Levin syndrome. Use of the VEPTR™ allowed these children who previously were at high risk for early demise due to restrictive lung disease to prolong their lives by allowing for thoracic volume growth and pulmonary development that was previously restricted due to their chest deformities.

The VEPTR™ has been demonstrated to increase lung volumes and correct spinal deformity but does have a fairly high incidence of complications. These include infection, broken ribs, movement of implants, nerve injury, and prominence causing pain.

VEPTR™ relies on attachment sites on the ribs proximally and either distal ribs, spine or iliac wings distally based on the pathology being treated. Either hooks or pedicle screws can be used for spinal anchoring; hooks are usually used for anchoring on the iliac wings. Each site is attached to a rod and they telescope on each other to allow for expansions over time. If there are significant rib fusions, a thoracoplasty with separation of the ribs is also usually done at time of VEPTR™ insertion. The goal of VEPTR™ insertion is to correct spinal and chest deformity without fusing the spine. While children are growing, VEPTR™ is generally expanded every 6-12 months in the operating room.

Related Reading

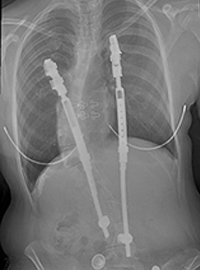

Growing Rods

Growing rods are placed along a child's spine and connected to anchors on the spine. The term is a misnomer as the rods don't "grow" but require surgery periodically to increase the construct length. The spine anchors can be hooks or pedicle screws and are placed above and below the curve. The anchored area at both ends is fused to provide strong support. The curved part of the spine remains unfused. Rods are attached on each side of the spine to the proximal and distal anchors. The rods connect either with a bracket that allows rod overlap or a central adaptor that connects the rods. Similar to the VEPTR™, growing rods help correct spine and chest deformity and need to be lengthened every 6-12 months in the operating room.

Growing rods are placed along a child's spine and connected to anchors on the spine. The term is a misnomer as the rods don't "grow" but require surgery periodically to increase the construct length. The spine anchors can be hooks or pedicle screws and are placed above and below the curve. The anchored area at both ends is fused to provide strong support. The curved part of the spine remains unfused. Rods are attached on each side of the spine to the proximal and distal anchors. The rods connect either with a bracket that allows rod overlap or a central adaptor that connects the rods. Similar to the VEPTR™, growing rods help correct spine and chest deformity and need to be lengthened every 6-12 months in the operating room.

In contrast to VEPTR™ which was developed for syndromic scoliosis and is now being used by surgeons for other diagnoses, growing rods were developed for idiopathic scoliosis and now is being used by surgeons for syndromic and congenital scoliosis. They have similar risks to VEPTR™ including infection, movement of implants, nerve injury, inadvertent spinal fusion, and prominence causing pain.

Related Reading

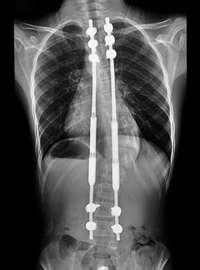

MAGEC™

MAGEC™ rods are a specific type of growing rods. They are implanted in a similar manner to VEPTRs and growing rods. Surgeons can decide to pair this rod with other implant systems that attach to the spine including pedicle screws, hooks, wires, and anchors from the VEPTR™ system. An innovative and unique feature of MAGEC™ rods are that they may be lengthened with the use of an external magnetic controller without the patient having to undergo an invasive procedure or even be placed under anesthesia. The surgeon or his or her staff perform the lengthening in the doctor's office. Due to the relative ease of the lengthening experience, many surgeons adopt a schedule of implant lengthening that is more frequent than the every five to six months used in VEPTRs™ and growing rods. Risks of MAGEC™ rods include the risks associated with VEPTRs™ and growing rods in addition to the risk of failure of the mechanical aspects of the lengthening mechanism.

MAGEC™ rods are a specific type of growing rods. They are implanted in a similar manner to VEPTRs and growing rods. Surgeons can decide to pair this rod with other implant systems that attach to the spine including pedicle screws, hooks, wires, and anchors from the VEPTR™ system. An innovative and unique feature of MAGEC™ rods are that they may be lengthened with the use of an external magnetic controller without the patient having to undergo an invasive procedure or even be placed under anesthesia. The surgeon or his or her staff perform the lengthening in the doctor's office. Due to the relative ease of the lengthening experience, many surgeons adopt a schedule of implant lengthening that is more frequent than the every five to six months used in VEPTRs™ and growing rods. Risks of MAGEC™ rods include the risks associated with VEPTRs™ and growing rods in addition to the risk of failure of the mechanical aspects of the lengthening mechanism.

Related Reading

Vertebral Body Tethering

Tethering attempts to straighten the spine by altering the growth of the spine without a definitive fusion. Screws are inserted on the outside of the vertebrae which connect a flexible cord along the spine. As the cord is tightened during surgery and as the child grows, the tether will help to adjust and straighten the curved spine. Tethering can often be done using small incisions in the chest utilizing a video camera. To learn more about this procedure, click here.

Tethering attempts to straighten the spine by altering the growth of the spine without a definitive fusion. Screws are inserted on the outside of the vertebrae which connect a flexible cord along the spine. As the cord is tightened during surgery and as the child grows, the tether will help to adjust and straighten the curved spine. Tethering can often be done using small incisions in the chest utilizing a video camera. To learn more about this procedure, click here.

Related Reading

Other Alternatives

Shilla™

The Shilla technique involves doing a short spinal fusion at the most curved portion (apex) of the spine using pedicle screws and rods. The rods are attached then at the top and bottom of the spine to pedicle screws without locking plugs that allow for continued growth of the spine. The rods "slide" through the screws at the proximal and distal ends. The Shilla technique remains experimental, with limited data about its effectiveness. Insertion of pedicle screws successfully and safely requires a high degree of technical skill and experience. Inadvertent fusion of the spine away from the apex is a risk. The benefit of the Shilla technique is that if successful it does not require repeat trips to the operating room for expansion as is necessary with both VEPTR™ and growing rods. Complications of the Shilla technique are similar to growing rods and VEPTR. Availability of the special screws and rods needed for Shilla technique are limited in the United States.

The Shilla technique involves doing a short spinal fusion at the most curved portion (apex) of the spine using pedicle screws and rods. The rods are attached then at the top and bottom of the spine to pedicle screws without locking plugs that allow for continued growth of the spine. The rods "slide" through the screws at the proximal and distal ends. The Shilla technique remains experimental, with limited data about its effectiveness. Insertion of pedicle screws successfully and safely requires a high degree of technical skill and experience. Inadvertent fusion of the spine away from the apex is a risk. The benefit of the Shilla technique is that if successful it does not require repeat trips to the operating room for expansion as is necessary with both VEPTR™ and growing rods. Complications of the Shilla technique are similar to growing rods and VEPTR. Availability of the special screws and rods needed for Shilla technique are limited in the United States.

Related Reading

Stapling

Stapling of the spine is a technique that acts like an "internal brace" for the spine and can help correct scoliosis through altering the growth pattern of the spine. A metal staple is inserted on one side of the curved spine to limit its growth. It can often be done through small incisions in the chest utilizing a video camera. The best patients for stapling are those with modest sized scoliosis who do not have rib and spine malformations. Stapling is not approved by the FDA and is only offered at a limited number of hospitals. Ask your doctor if they utilize this technique.

Stapling of the spine is a technique that acts like an "internal brace" for the spine and can help correct scoliosis through altering the growth pattern of the spine. A metal staple is inserted on one side of the curved spine to limit its growth. It can often be done through small incisions in the chest utilizing a video camera. The best patients for stapling are those with modest sized scoliosis who do not have rib and spine malformations. Stapling is not approved by the FDA and is only offered at a limited number of hospitals. Ask your doctor if they utilize this technique.

Related Reading

Alternative Techniques

There are many other proposed treatment methods for early onset scoliosis. These include chiropractic care, acupuncture, stretching, and massage. Various braces, medications, exercise programs that propose to treat early onset scoliosis are also easily found on the internet. All of these various methods have not been scientifically studied and have not been demonstrated to show effectiveness in treating scoliosis. They often require significant out of pocket financial investment. These alternative treatments may have a role in reduction of discomfort, but are not believed to alter the natural history of early onset scoliosis.

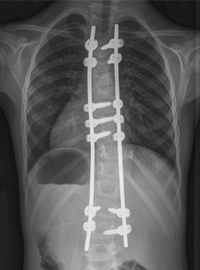

Spine Fusion

In some cases, spinal fusion may be indicated for a child with early onset scoliosis. Long fusions, especially in the thoracic spine, have been largely abandoned in young children because of the adverse affect on long-term pulmonary function. Fusion of the thoracic spine will stop longitudinal growth of the chest. Research has demonstrated adverse effects on pulmonary function in adolescence for children who had extensive spinal fusion at a young age

In some cases, however, a short fusion may be appropriate to try and prevent more serious progression of scoliosis. Short fusion is also done as part of the Shilla technique and the growing rod technique.

Usually a short fusion of the spine is done when a child has a hemivertebra. Most surgeons are now comfortable removing a hemivertebra and doing a short segment spinal fusion to stabilize the spine from a posterior incision. In many cases this can completely straighten the spine and prevent need for future surgeries. Usually at most a brace will be used for postoperative immobilization, however, if the surgeon cannot get adequate spinal fixation a cast may be required for 3-6 months to hold alignment while the spine fuses.

Related Reading

Referring Patients

When to Refer

When you have a suspicion that a patient has Early Onset Scoliosis (EOS), it is appropriate to refer to an orthopedic surgeon as soon as possible. Some types of treatment such as casting or bracing are age and time sensitive, with higher efficacy for younger patients and earlier initiation of treatment.

Studies to acquire

It is reasonable to get a full-length standing spine PA and lateral X-rays prior to sending a patient to see the orthopedic specialist. If the child cannot stand, then a full-length sitting spine AP and lateral X-rays are appropriate. If the child cannot sit or stand, then supine AP and lateral spine films are reasonable. The orthopedic surgeon may send the patient for further studies after evaluation, such as CT scan or MRI if needed. However, not all patients require advanced imaging beyond X-rays and this should be reserved for patients who have already been evaluated by the orthopedic specialist.

Who to refer to

Early Onset Scoliosis is relatively rare, and thus should be sent to a specialist who sees and treats patients with this condition frequently. All members of the Children's Spine Study Group are versed in current treatments and concepts for EOS and would be appropriate for referral. For a complete list of physicians associated with the Pediatric Spine Study Group, please visit our Study Group page.

Talking to Families

Discussing EOS with Families

The diagnosis of early onset scoliosis is often overwhelming to parents with a young child. Most parents will have little, if any, understanding about the diagnosis and future treatments. This always requires a careful discussion to provide a framework for future referrals, imaging, and options for treatment. Most curves will require referral to a specialist who treats early onset scoliosis. Parents are always reassured to know that these curves, regardless of how severe, have options for treatment. It is also helpful to let them know that most treatments allow children to live a normal, active life. Referral to reliable online resources such as this website will give the family a source of good information rather than a Google search which is often more confusing than helpful.

Additional Resources